" The more well-known you are as an artist for a particular style or flavour, the more scared you become of breaking the boundaries of your own construction. You need to constantly walk in the face of failure. " Alexander James Hamilton.

INTERVIEW:

Alexander James talks about his 'Oil + Water' project created in Siberia with Anna Prosevtova of Russian Arts & Culture.

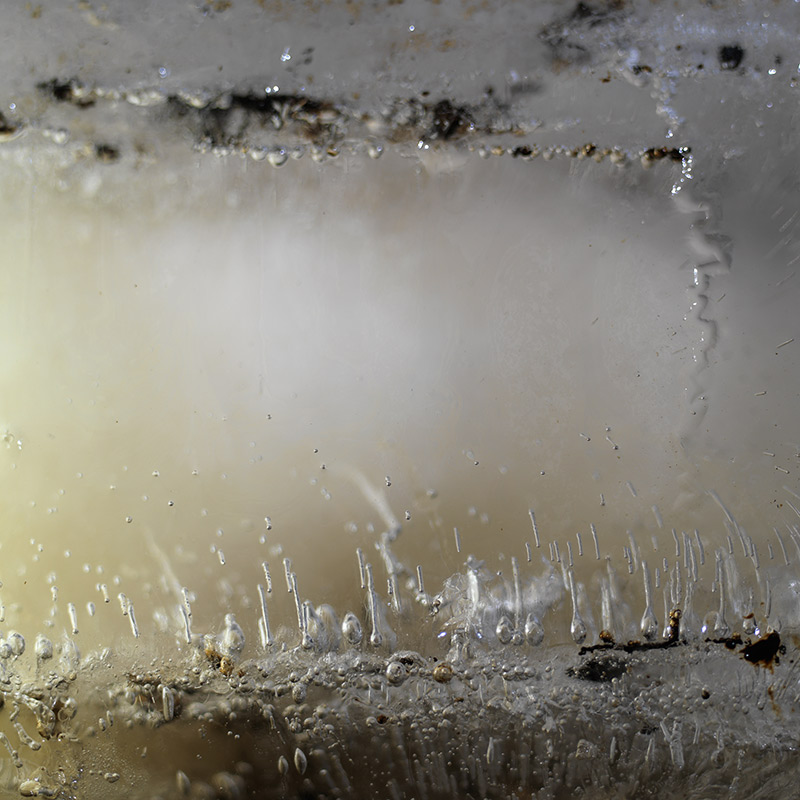

'Ptolemy', from 'Oil + Water' 2015.

Alexander James Hamilton is an artist working on a cross-road of media, combining painting, photography and sculpture. Using water and environment as his medium for thirty years, Alexander has recently completed a new project – 'Oil and Water', executed in Siberia. Creating physical forms out of solidified crude oil and then entombing them in an ossuary of frozen river water, the artist explores the relationship between these two resources, central to the survival and industrial development of the human species.

We met with Alexander to talk about his project, time in Russia and the role of an artist today.

Anna Prosvetova: Alexander, you have been working in many locations around the world but two of your recent projects were completed in Moscow and Siberia. Why did you become so interested in Russia?

Alexander James: Thats a great place to start, if you take a small reproduction of say a Constable painting onto the street and stop a hundred random people in London to ask the name of that painting or even the artist, you would not find one person who can answer I am sure. When I first went to Russia I attended a dinner at the British Embassy in Moscow. earlier that day I visited the Tretyakov gallery and saw one painting that I just felt in love with: Princess Tarakanova by Konstantin Flavitsky. I had a reproduction of this painting with me when I went to that dinner, and I could not take my eyes of it. A member of staff at the dinner spotted it and knew the story behind the painting, where it was hanging and the history of the period in general. All the staff and all of the russian guests at the event knew the piece; they were from all from different backgrounds and knew the story all too well. Such situations are like a drug to an artist, and I was hooked; it is just not like that in the west. I have had many exhibitions prior to coming to Russia but 'Rastvoyrenayya Pechal' in Moscow held at Triumph gallery was special, showing over 30 years of analogue photographic exploring a lifelong dedication. I think for any serious artist throughout the ages there has always been a dialog of great importance with certain countries and certain periods of political uncertainty. Russia does not really care to be fashionable at all in the world of art, but they do care about a life dedicated to the arts. They understand, that if give your body and soul to the artistic practice, this is something every Russian would want to learn about.

Princess Tarakanova, 1864, by Konstantin Flavitsky / Courtesy of Tretyakov Gallery

AP: How did the project Oil + Water come about?

AJ: This project is different from my previous work. There was no intention to exhibit the work, I thought it was doomed to fail; it was an intention to do something that has never been done before; highly experimental and with wild elements to ruin any planed outcome. I gave my word to a curator in St Petersburg at a dinner one evening; that I would come back to do a project in Siberia that no one has even dreamed of. He asked me: “When?” I have answered: “this winter.” He called me crazy, a statement that everyone at the table agreed with, because by this time I had already driven a ten-ton truck with my entire studio from London to Moscow. “Everyone thinks that you are insane, but they may come to love you for it if you dont die first.”

I have but three things to offer in life: my word, my hand and my work, and I value them all equally. It seems this goes a long way in Russia as well. I do not want to be political, but at the moment it seems that we are having so many battles over the access to oil and water. I have known for thirty years now that water management policies, local and global, are shocking if you look into it. Over three quarters of Australia’s private land over fresh water springs are owned by one of three corporations. The state of Ohio in the USA has been dry for years; in Barcelona half of its water is produced by a nuclear desalination process, the writing is on the wall.

After thirty years of creating sculptural works under water, I thought that Siberia an important place to base my next project. Siberia has biblical reserves of both water flooding down from the Mongolian plains and crude oil, with the scale of the territory and everything I sought in plain sight, the stage was set. I travelled to Krasnoyarsk last year by train looking for suitable sites, I have a lot of good friends in Siberia, but I had extended it a little bit further this time to find the right mix. I had to setup three studios: one was in Krasnoyarsk, in a boathouse dragged onto the iceflow of the Yenesei River; one was high up in the Ural mountain deep in the northern planes, and the other was in Perm, the oil town. The reason I did this is because I really needed the right conditions, and I travelled between them depending on which one was the coldest at the given time. I was looking to work in Minus 50 degree conditions or the project would fail. I was very lucky, because I managed to collaborate with connections to gain acces to crude oil through one of the local oil companies. This was all done very discretely, without any financial remuneration or cross-pollination of any kind; they were as interested as I in the possible outcome. I just let them know when I was coming, and they were remarkably helpful in giving me access to the black gold that has sent man to war for a century, tapped straight from the ground to the studio.

AP: What was your process of working? Did you have a team to assist you in Siberia?

AJ: I was working very much alone on this project nobody would be crazy enough to sign up for this, the nature and the scale of this differed greatly from my previous expeditions, it was seriousley dangerous. I had a team of assistants in Moscow when I was working the Triumph Gallery show, because figurative work is incredibly complex for me to realise. You are working in two hundred-ton tanks of water, a hand fabricted wardrobe and extensive props all made by hand. I was lucky, because Russia has a huge amount of creative talent, and all my team were local and we are still friends today. But no Russian wanted to accompany me to a log cabin sitting on the ice flow of the Yenesei, you only had to see their faces when the suggestion was made to have your answer, so for Oil + Water I was alone.

'Jupiter', from 'Rastvorennaya Pechal' (Distil Ennui) exhibition Moscow. 2014

AP: In your artworks you always use liquid water. Was it different this time to work with the frozen water?

AJ: My process is a mixture between painting, sculpture and photography. I create all my works underwater, working with the surface tension of the water I use a paintbrush to cause deflections; literally painting with light. This time it was a very different process. I did not really know much about how the 'enthalpy of fusion' process would go; it was a new area for me and very little information was out there to guide me. I found it fascinating; I was like a child. Creating a 1 metre block formation of water and freezing it quickly forms a steel like vault of ice around the oil subject inside, the process created immense pressure as the ice tomb closed in. The trapped gas pockets form and are released during in the process, you could hear & see explosions within the ice as the compressed energy finds a way to escape and move in its search to be released.

It was like capturing fireworks within the ice; each bubble acting like a gun going off. I had a microphone, embedded into the ice, and you can hear that it is a violent moment, though you would not think so. I also have videos for each work, with the oil gently melting: it is the most beautiful thing. I found it interesting to work with ice. One reacts very differently to this kind of work. You walk up to such ice sculptures; they are very large and heavy. The frost clouds its surface and you do not really see what is inside for the first moment; it looks like a dirty piece of glass. But all of a sudden you realize what this is, what is going on inside the ice. I think the fact that the object exists only because of your personal endeavour, your personal effort in itself is quite a dictum to process: I like working and presenting outside of the standard gallery framework.

AP: In all your projects you cultivate your flowers and hand make the objects involved before placing them into the final work underwater. How did you come about this idea, this process? Why is it important for you to grow a flower?

AJ: I believe that if you want something as an artist that is period or dialogue specific, where no questions of the provenance of the work are raised about its quality then no measure is too much, no process too long if the results convey that purity. There are fewer and fewer true Renaissance artists these days. Many are using the exact same materials in their work which I find intellectually insulting, going to the store and buying the same colour blue that every other artist uses. Who these days actually mix their own paints? Who makes their own canvas stretchers? Who does anything in the studio that is truly of a craftsmanship level, as, for example, the eggs of Faberge? I want people to come to my studio and see a real craftsman at work no matter what is underway.

People usually want two things from me: my time or my work, and I have got very little of both. I have already spent thirty years, bouncing between gallery and museum circles, and it has not been a joyous experience. The only thing I ask is that if they are going to spend time and be resolute about what it is I am doing, at least I gain an understanding from it what is the point if not shared. I do not really want Tate Britain or Tate Modern to come to my studio to see my work, because if you accept this form of institutional art into your practice, you would become an institutional artist cowering to their will. But I do not want to create the same thing for the next ten years. I want something that physically and mentally challenges me. The more well-known you are the more scared you become of breaking the boundaries of your own construction. You need to walk in the face of failure, you really do. For this Oil and Water project I had to experiment with the process in the field raw and exposed, because there is no way of finding out the results before hand; it has never been done before. I just thought: “Why not!” I am not going to change my practice just to suit someone else; so really anything becomes a possibility, what a wonderful proposition.

AP: What is your background? Were you trained as an artist?

AJ: I am completely unsullied by the world of academia. I left home when I was very young, and by the time I was sixteen I was living rough on a beach in the Carribiean creating unseen works still to this day. I have relocated my entire studio to seventeen different countries to date. What could anyone want to teach me that I could not teach myself ? If you need a new skillset for a project; be it welding, cold forging, electronics, lighting, painting absolutely anything then just get on and do it, simple really. One example, I drove a very famous Krasnoyarsk October grand piano all the way back from Russia to my studio in London: I still do not know how to play it, but I will learn when I have time. Everything is possible; what you need is time and a reason for wanting to do it; although time seems to be my enemy now... I have so much I still need to do, the journey still has a long path ahead of me. time for sleep comes later.

'Dark Matter' from 'Oil + Water', Siberia. 2015

AP: I was intrigued by the description of 'Oil + Water' where you mentioned that you have been returning the frozen blocks of water and oil to the original locations in the forest, where the oil came out of the ground. Why did you decide to do it?

AJ: Yes, it was in the forest where the materials all began so a fitting location I believe for the pieces to end up. I was working outside all day; ten hours a day at -50°C. It was absurd, but it was the only way to be actually able to do it. For example, this particular piece, Dark Matter. It is a two-foot perfect sphere of oil. It was formed outside where the oil became molasis thick holding its shape to be set inside an ossuary of a frozen river water, with the oil formation in the centre. The saddest thing was that I could not take these things back home with me, because the sculptures themselves were so beautiful to me; they felt like my children as does all my work; I am terrible parent abandonning my kids like that. I carefully dragged each piece by quad bike, snowmobile or tractor into the forest each with its own place and let them become one with the environment. I am thinking about them right now, its beautiful to drift through the forest and see in your mind how they are melting and refreezing now with the cycle of day and night. It would be wonderful to go back and be with them again.

AP: Have you been influenced by Russian culture during your time in the country?

AJ: Of Course; countless times on many levels. most recently I have seen an exhibition in Perm, at the museum of contemporary art. It was a great show and someone was using black water reflections kind of like what I do sometimes terrific! Of course, I have been influenced in general by the environment, people and the culture. It has already influenced my studio in London; there are new flavours of work coming through. Bear in mind, that my aesthetic is black. For thirty years my works have been sold to collectors around the world, and black is the predominant aestetic. Now I think perhaps it is changing somehow, they always say: “Never confuse your audience” and I think I am confusing everyone with this new project - there is very little black to be seen anywhere.

'Intervene' from 'Oil + Water' Siberia. 2015.

As for Russian art, I have also been a great fan of Kandinsky and Vavilov, but to be impressed by a single piece by any artist, I think, is a rather naive notion. We can all hit or miss once in a while but to consider an artist properly you must consider at least three pieces to confirm their signature, and I just hope to only ever see these three. I don't have time to waste.

AP: You started using social media recently to showcase your work. Do you use it to get a creative inspiration?

AJ: No, I do not use social media to get inspiration at all. I did not even go to exhibitions for the first fifteen years of my career. We are all sponges, and the younger we are the more absorbent we are; and I didnt want that influence in my developing years, it was a serious fear that I was very concious of. Now I have changed and try to see everything, but I am not a sponge anymore I am getting older. I know what is there and what is missing. I collect myself, but I have different reasons for doing that. I think social media is a great way to get the word out. I have been creating for thirty years and I am getting recognised now, but I love being able to accelerate that and get my message across; nothing more. It is important. Rauschenberg painted billboards in Hollywood. One thing he said about it was: “I may be a great artist to you, it's your opinion. To make art is something really it is, but to get the art seen is more; especially right now where we are so visually swamped.” This is really of value, because I believe in the aesthetic of traditionalism. I believe that actually something has to be earnestly beautiful.. when you know the artist has suffered during its creation. Many contemporary works show no craftsmanship; they show nothing other than a need for publicity. So to get work that I think is of value, seen without the hype or fashionable connections; to get that work seen is really exciting.

AP: What are your future projects? And where are you going to move your studio next?

AJ: I am deeply satisfied with the outcome of 'Oil + Water'; I am thinking about showing the project in Russia, but it is not decided yet. Now I want to sit with the works and enjoy them before they leave the studio. I am planning to go back to Russia, I still have a space there I can work from. I am a great believer that if you say something, you must follow it through 'mean what you say, and say what you mean'. There are two projects on the table right now, and if I disclose both of them, I will have to do both of them, so I will keep it to myself for now.

AP: Alexander, thank you!